Part IIIPersuasion

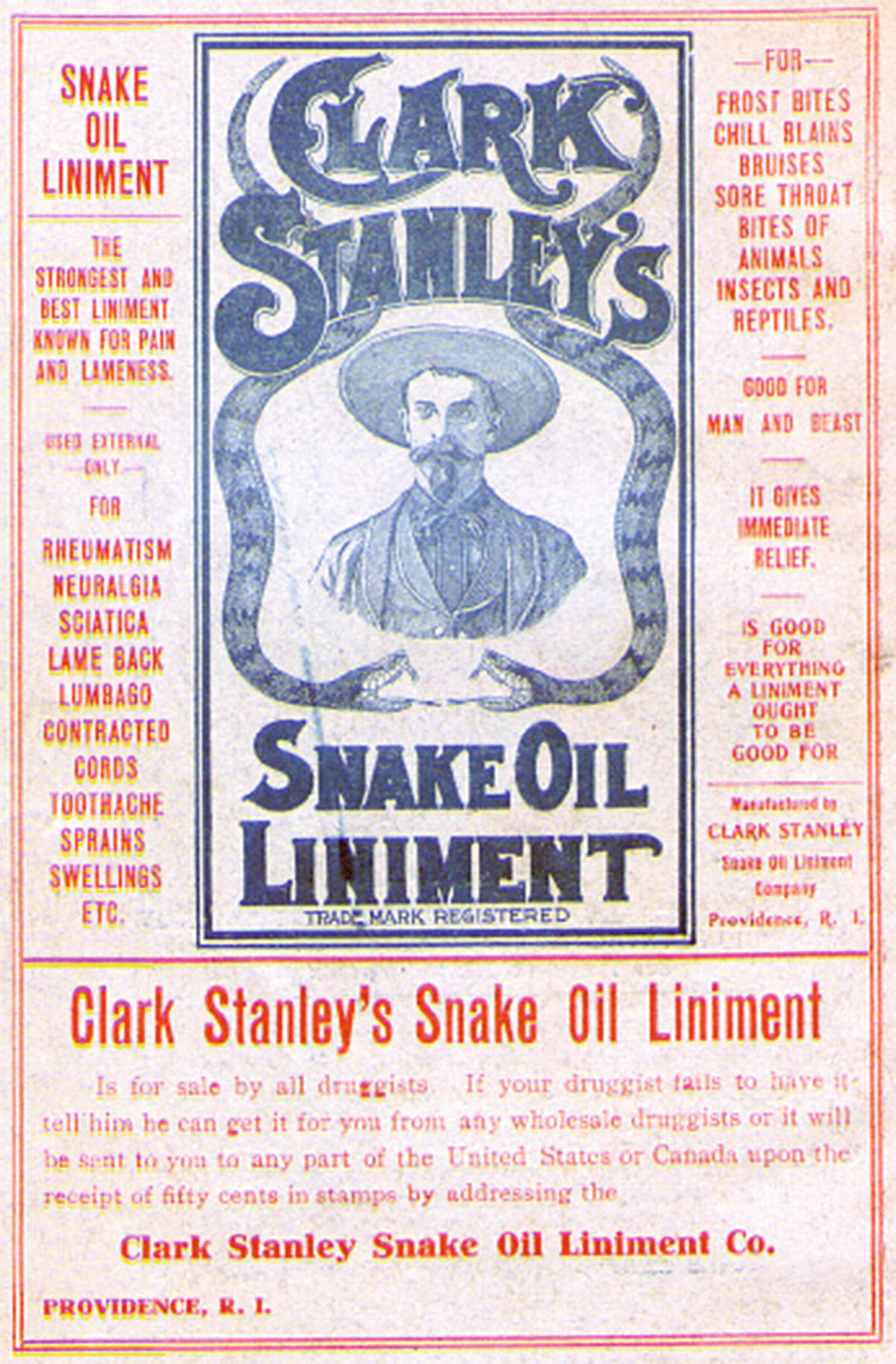

With drugstores dotting our neighborhoods like neon-lit aid stations, we sometimes forget that reliable medication was not always so obtainable. In the 1860s, patent medicine blanketed the American West. Cure-alls, such as Dr. William’s Pink Pills for Pale People1 made out of Epsom salt and rust, claimed to offer comfort for ailments ranging from “loss of vital forces,” St. Vitus’s Dance,2 and “all female weakness”—medically questionable but certainly unenviable afflictions. The era marked a time in American history, as well as the history of persuasion.

The late 1800s was also the golden age of railroads. The tracks of the First Transcontinental Railroad laid across nearly 2,000 miles of plains, hills and mountains stretching from San Francisco, California to Council Bluffs, Iowa. Millions of pounds of iron, steel, and timber, along with the strenuous efforts of thousands of workers, connected the sandy shores of the Pacific to the prairies of America’s heartland. Many of the laborers hailed from China.

Artist’s rendering of Chinese sea snake

Clark Stanley’s Snake Oil Liniment, c. 1905, promising immediate relief from everything from frost bite to rheumatism3.

To be persuaded is to be human. Every generation, class, and culture is a laboratory of influence. We must ask ourselves why we are persuaded. Why do the mysterious forces of desire, selection, and positioning influence our decisions? Moreover, we must ask ourselves how can we use persuasion to help rather than hinder, and guide rather than misguide.

We begin by discussing the fundamental concepts of persuasion: empathy, authority, motivation, relevancy, and reciprocity. Next, we take a page from the book of marketing and cover the “Four Ps”: product, price, promotion, and place. Lastly, we answer the questions of why do consumers buy, and how users achieve their goals. In this pursuit, we focus our efforts on crafting good experiences; but, we cannot rely on craftsmanship alone; sometimes we must persuade.